Who Was the First Person to Read Old Egyptian Writings

Ancient Egyptian literature was written in the Egyptian linguistic communication from aboriginal Egypt's pharaonic period until the end of Roman domination. It represents the oldest corpus of Egyptian literature. Along with Sumerian literature, it is considered the world's earliest literature.[1]

Writing in aboriginal Arab republic of egypt—both hieroglyphic and hieratic—starting time appeared in the late 4th millennium BC during the belatedly phase of predynastic Egypt. By the Old Kingdom (26th century BC to 22nd century BC), literary works included funerary texts, epistles and letters, hymns and poems, and commemorative autobiographical texts recounting the careers of prominent administrative officials. Information technology was not until the early Center Kingdom (21st century BC to 17th century BC) that a narrative Egyptian literature was created. This was a "media revolution" which, according to Richard B. Parkinson, was the result of the rise of an intellectual class of scribes, new cultural sensibilities about individuality, unprecedented levels of literacy, and mainstream access to written materials.[2] However, it is possible that the overall literacy rate was less than one percent of the unabridged population. The cosmos of literature was thus an aristocracy do, monopolized by a scribal class attached to regime offices and the imperial court of the ruling pharaoh. However, there is no total consensus among mod scholars concerning the dependence of ancient Egyptian literature on the sociopolitical order of the majestic courts.

Middle Egyptian, the spoken language of the Eye Kingdom, became a classical language during the New Kingdom (16th century BC to 11th century BC), when the vernacular linguistic communication known as Late Egyptian start appeared in writing. Scribes of the New Kingdom canonized and copied many literary texts written in Centre Egyptian, which remained the linguistic communication used for oral readings of sacred hieroglyphic texts. Some genres of Heart Kingdom literature, such as "teachings" and fictional tales, remained popular in the New Kingdom, although the genre of prophetic texts was not revived until the Ptolemaic period (4th century BC to 1st century BC). Popular tales included the Story of Sinuhe and The Eloquent Peasant, while important teaching texts include the Instructions of Amenemhat and The Loyalist Teaching. By the New Kingdom menstruation, the writing of commemorative graffiti on sacred temple and tomb walls flourished as a unique genre of literature, nonetheless it employed formulaic phrases similar to other genres. The acknowledgment of rightful authorship remained of import only in a few genres, while texts of the "teaching" genre were pseudonymous and falsely attributed to prominent historical figures.

Ancient Egyptian literature has been preserved on a wide diverseness of media. This includes papyrus scrolls and packets, limestone or ceramic ostraca, wooden writing boards, monumental stone edifices and coffins. Texts preserved and unearthed by modern archaeologists stand for a small fraction of ancient Egyptian literary material. The area of the floodplain of the Nile is under-represented because the moist environs is unsuitable for the preservation of papyri and ink inscriptions. On the other hand, hidden caches of literature, buried for thousands of years, take been discovered in settlements on the dry out desert margins of Egyptian civilization.

Scripts, media, and languages [edit]

Hieroglyphs, hieratic, and Demotic [edit]

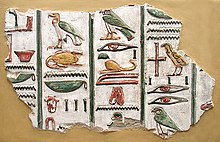

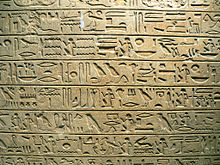

By the Early Dynastic Period in the belatedly 4th millennium BC, Egyptian hieroglyphs and their cursive grade hieratic were well-established written scripts.[4] Egyptian hieroglyphs are small creative pictures of natural objects.[5] For example, the hieroglyph for door-commodities, pronounced se, produced the s sound; when this hieroglyph was combined with another or multiple hieroglyphs, it produced a combination of sounds that could represent abstract concepts similar sorrow, happiness, dazzler, and evil.[half dozen] The Narmer Palette, dated c. 3100 BC during the last phase of Predynastic Egypt, combines the hieroglyphs for catfish and chisel to produce the name of King Narmer.[vii]

The Egyptians called their hieroglyphs "words of god" and reserved their use for exalted purposes, such as communicating with divinities and spirits of the dead through funerary texts.[8] Each hieroglyphic word represented both a specific object and embodied the essence of that object, recognizing it equally divinely made and belonging within the greater cosmos.[9] Through acts of priestly ritual, like burning incense, the priest allowed spirits and deities to read the hieroglyphs decorating the surfaces of temples.[ten] In funerary texts beginning in and following the Twelfth Dynasty, the Egyptians believed that disfiguring, and even omitting certain hieroglyphs, brought consequences, either good or bad, for a deceased tomb occupant whose spirit relied on the texts equally a source of nourishment in the afterlife.[eleven] Mutilating the hieroglyph of a venomous ophidian, or other unsafe beast, removed a potential threat.[11] However, removing every instance of the hieroglyphs representing a deceased person's name would deprive his or her soul of the power to read the funerary texts and condemn that soul to an inanimate beingness.[11]

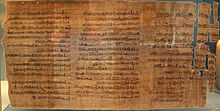

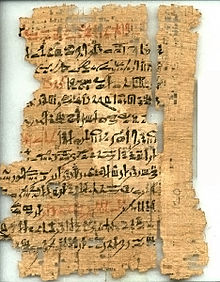

Hieratic is a simplified, cursive form of Egyptian hieroglyphs.[12] Like hieroglyphs, hieratic was used in sacred and religious texts. By the 1st millennium BC, calligraphic hieratic became the script predominantly used in funerary papyri and temple rolls.[13] Whereas the writing of hieroglyphs required the utmost precision and care, cursive hieratic could exist written much more quickly and was therefore more than practical for scribal record-keeping.[14] Its primary purpose was to serve as a autograph script for non-royal, non-monumental, and less formal writings such as individual letters, legal documents, poems, tax records, medical texts, mathematical treatises, and instructional guides.[15] Hieratic could be written in two different styles; ane was more than calligraphic and usually reserved for regime records and literary manuscripts, the other was used for informal accounts and letters.[16]

Past the mid-1st millennium BC, hieroglyphs and hieratic were still used for regal, monumental, religious, and funerary writings, while a new, even more cursive script was used for informal, day-to-day writing: Demotic.[xiii] The final script adopted by the aboriginal Egyptians was the Coptic alphabet, a revised version of the Greek alphabet.[17] Coptic became the standard in the fourth century Ad when Christianity became the state organized religion throughout the Roman Empire; hieroglyphs were discarded every bit idolatrous images of a pagan tradition, unfit for writing the Biblical canon.[17]

Writing implements and materials [edit]

Egyptian literature was produced on a diversity of media. Along with the chisel, necessary for making inscriptions on stone, the chief writing tool of aboriginal Arab republic of egypt was the reed pen, a reed fashioned into a stem with a bruised, brush-similar end.[18] With pigments of carbon black and red ochre, the reed pen was used to write on scrolls of papyrus—a thin material made from chirapsia together strips of pith from the Cyperus papyrus plant—as well as on pocket-sized ceramic or limestone potsherds known every bit ostraca.[19] Information technology is thought that papyrus rolls were moderately expensive commercial items, since many are palimpsests, manuscripts that have had their original contents erased to make room for new written works.[twenty] This, forth with the practice of tearing pieces off of larger papyrus documents to make smaller messages, suggests that there were seasonal shortages acquired by the express growing season of Cyperus papyrus.[20] It as well explains the frequent utilise of ostraca and limestone flakes equally writing media for shorter written works.[21] In addition to stone, ceramic ostraca, and papyrus, writing media also included wood, ivory, and plaster.[22]

Past the Roman Period of Egypt, the traditional Egyptian reed pen had been replaced past the main writing tool of the Greco-Roman earth: a shorter, thicker reed pen with a cut nib.[23] Likewise, the original Egyptian pigments were discarded in favor of Greek lead-based inks.[23] The adoption of Greco-Roman writing tools influenced Egyptian handwriting, as hieratic signs became more than spaced, had rounder flourishes, and greater angular precision.[23]

Preservation of written textile [edit]

Underground Egyptian tombs built in the desert provide possibly the virtually protective environment for the preservation of papyrus documents. For example, in that location are many well-preserved Volume of the Dead funerary papyri placed in tombs to human action as afterlife guides for the souls of the deceased tomb occupants.[24] However, it was only customary during the late Middle Kingdom and showtime half of the New Kingdom to place non-religious papyri in burying chambers. Thus, the majority of well-preserved literary papyri are dated to this menses.[24]

Most settlements in ancient Egypt were situated on the alluvium of the Nile floodplain. This moist environment was unfavorable for long-term preservation of papyrus documents. Archaeologists have discovered a larger quantity of papyrus documents in desert settlements on country elevated above the floodplain,[25] and in settlements that lacked irrigation works, such as Elephantine, El-Lahun, and El-Hiba.[26]

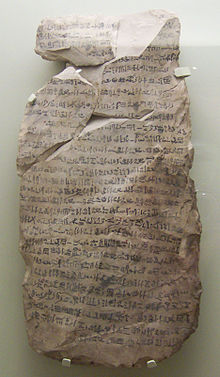

Writings on more than permanent media have also been lost in several ways. Stones with inscriptions were frequently re-used equally edifice materials, and ceramic ostraca require a dry out environment to ensure the preservation of the ink on their surfaces.[27] Whereas papyrus rolls and packets were unremarkably stored in boxes for safekeeping, ostraca were routinely discarded in waste pits; one such pit was discovered by chance at the Ramesside-era village of Deir el-Medina, and has yielded the majority of known individual letters on ostraca.[21] Documents establish at this site include messages, hymns, fictional narratives, recipes, business receipts, and wills and testaments.[28] Penelope Wilson describes this archaeological discover as the equivalent of sifting through a mod landfill or waste container.[28] She notes that the inhabitants of Deir el-Medina were incredibly literate by ancient Egyptian standards, and cautions that such finds only come "...in rarefied circumstances and in detail conditions."[29]

John W. Tait stresses, "Egyptian cloth survives in a very uneven fashion ... the unevenness of survival comprises both time and space."[27] For case, there is a famine of written material from all periods from the Nile Delta only an affluence at western Thebes, dating from its heyday.[27] He notes that while some texts were copied numerous times, others survive from a single copy; for instance, there is simply i complete surviving copy of the Tale of the shipwrecked sailor from the Middle Kingdom.[xxx] Yet, Tale of the shipwrecked crewman also appears in fragments of texts on ostraca from the New Kingdom.[31] Many other literary works survive simply in fragments or through incomplete copies of lost originals.[32]

Classical, Heart, Late, and Demotic Egyptian language [edit]

Although writing first appeared during the very late quaternary millennium BC, information technology was simply used to convey short names and labels; continued strings of text did not appear until about 2600 BC, at the beginning of the Old Kingdom.[33] This development marked the beginning of the first known phase of the Egyptian language: Old Egyptian.[33] Old Egyptian remained a spoken language until about 2100 BC, when, during the beginning of the Middle Kingdom, information technology evolved into Middle Egyptian.[33] While Heart Egyptian was closely related to Old Egyptian, Late Egyptian was significantly different in grammatical structure. Tardily Egyptian perchance appeared as a colloquial language as early equally 1600 BC, but was not used equally a written linguistic communication until c. 1300 BC during the Amarna Period of the New Kingdom.[34] Late Egyptian evolved into Demotic by the 7th century BC, and although Demotic remained a spoken language until the 5th century Advertisement, information technology was gradually replaced by Coptic offset in the 1st century Advertisement.[35]

Hieratic was used alongside hieroglyphs for writing in Onetime and Centre Egyptian, condign the dominant form of writing in Late Egyptian.[36] Past the New Kingdom and throughout the residuum of ancient Egyptian history, Center Egyptian became a classical linguistic communication that was usually reserved for reading and writing in hieroglyphs[37] and the spoken language for more exalted forms of literature, such equally historical records, commemorative autobiographies, hymns, and funerary spells.[38] All the same, Middle Kingdom literature written in Middle Egyptian was also rewritten in hieratic during later periods.[39]

Literary functions: social, religious and educational [edit]

Throughout aboriginal Egyptian history, reading and writing were the chief requirements for serving in public office, although government officials were assisted in their twenty-four hour period-to-day piece of work by an elite, literate social grouping known as scribes.[40] As evidenced past Papyrus Anastasi I of the Ramesside Catamenia, scribes could even be expected, according to Wilson, "...to organize the excavation of a lake and the building of a brick ramp, to establish the number of men needed to transport an obelisk and to adjust the provisioning of a military machine mission".[41] Besides government employment, scribal services in drafting letters, sales documents, and legal documents would have been frequently sought by illiterate people.[42] Literate people are idea to have comprised merely i% of the population,[43] the remainder beingness illiterate farmers, herdsmen, artisans, and other laborers,[44] also as merchants who required the assistance of scribal secretaries.[45] The privileged status of the scribe over illiterate transmission laborers was the subject of a popular Ramesside Menstruation instructional text, The Satire of the Trades, where lowly, undesirable occupations, for example, potter, fisherman, laundry human being, and soldier, were mocked and the scribal profession praised.[46] A similar demeaning mental attitude towards the illiterate is expressed in the Middle Kingdom Teaching of Khety, which is used to reinforce the scribes' elevated position within the social hierarchy.[47]

The scribal class was the social grouping responsible for maintaining, transmitting, and canonizing literary classics, and writing new compositions.[48] Archetype works, such as the Story of Sinuhe and Instructions of Amenemhat, were copied past schoolboys as pedagogical exercises in writing and to instill the required ethical and moral values that distinguished the scribal social class.[49] Wisdom texts of the "teaching" genre represent the majority of pedagogical texts written on ostraca during the Eye Kingdom; narrative tales, such equally Sinuhe and King Neferkare and General Sasenet, were rarely copied for school exercises until the New Kingdom.[50] William Kelly Simpson describes narrative tales such as Sinuhe and The shipwrecked sailor as "...instructions or teachings in the guise of narratives", since the chief protagonists of such stories embodied the accepted virtues of the day, such equally love of home or self-reliance.[51]

There are some known instances where those exterior the scribal profession were literate and had admission to classical literature. Menena, a draughtsman working at Deir el-Medina during the Twentieth dynasty of Egypt, quoted passages from the Middle Kingdom narratives Eloquent Peasant and Tale of the shipwrecked sailor in an instructional letter reprimanding his disobedient son.[31] Menena's Ramesside contemporary Hori, the scribal author of the satirical letter in Papyrus Anastasi I, admonished his leaseholder for quoting the Instruction of Hardjedef in the unbecoming manner of a non-scribal, semi-educated person.[31] Hans-Werner Fischer-Elfert farther explains this perceived amateur barb to orthodox literature:

What may be revealed by Hori's set on on the fashion in which some Ramesside scribes felt obliged to demonstrate their greater or lesser acquaintance with ancient literature is the conception that these venerable works were meant to be known in full and not to be misused every bit quarries for popular sayings mined deliberately from the past. The classics of the fourth dimension were to exist memorized completely and comprehended thoroughly earlier being cited.[52]

There is express simply solid evidence in Egyptian literature and art for the practice of oral reading of texts to audiences.[53] The oral operation word "to recite" (šdj) was commonly associated with biographies, letters, and spells.[54] Singing (ḥsj) was meant for praise songs, love songs, funerary laments, and certain spells.[54] Discourses such as the Prophecy of Neferti suggest that compositions were meant for oral reading amid aristocracy gatherings.[54] In the 1st millennium BC Demotic curt story cycle centered on the deeds of Petiese, the stories begin with the phrase "The vox which is earlier Pharaoh", which indicates that an oral speaker and audience was involved in the reading of the text.[55] A fictional audience of high authorities officials and members of the royal court are mentioned in some texts, but a wider, non-literate audience may have been involved.[56] For example, a funerary stela of Senusret I (r. 1971–1926 BC) explicitly mentions people who will gather and listen to a scribe who "recites" the stela inscriptions out loud.[56]

Literature also served religious purposes. Commencement with the Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom, works of funerary literature written on tomb walls, and later on on coffins, and papyri placed within tombs, were designed to protect and nurture souls in their afterlife.[57] This included the use of magical spells, incantations, and lyrical hymns.[57] Copies of non-funerary literary texts found in non-majestic tombs suggest that the dead could entertain themselves in the afterlife by reading these educational activity texts and narrative tales.[58]

Although the cosmos of literature was predominantly a male person scribal pursuit, some works are thought to have been written past women. For example, several references to women writing letters and surviving individual letters sent and received by women have been found.[59] Nonetheless, Edward F. Wente asserts that, even with explicit references to women reading messages, it is possible that women employed others to write documents.[lx]

[edit]

Richard B. Parkinson and Ludwig D. Morenz write that aboriginal Egyptian literature—narrowly defined equally belles-lettres ("cute writing")—was non recorded in written class until the early Twelfth dynasty of the Middle Kingdom.[61] Quondam Kingdom texts served mainly to maintain the divine cults, preserve souls in the afterlife, and document accounts for practical uses in daily life. Information technology was non until the Eye Kingdom that texts were written for the purpose of entertainment and intellectual marvel.[62] Parkinson and Morenz too speculate that written works of the Middle Kingdom were transcriptions of the oral literature of the Sometime Kingdom.[63] It is known that some oral poesy was preserved in afterward writing; for instance, litter-bearers' songs were preserved equally written verses in tomb inscriptions of the Old Kingdom.[62]

Dating texts by methods of palaeography, the report of handwriting, is problematic because of differing styles of hieratic script.[64] The use of orthography, the study of writing systems and symbol usage, is also problematic, since some texts' authors may have copied the characteristic style of an older archetype.[64] Fictional accounts were often ready in remote historical settings, the use of contemporary settings in fiction beingness a relatively contempo phenomenon.[65] The style of a text provides little help in determining an exact appointment for its composition, as genre and authorial option might exist more concerned with the mood of a text than the era in which it was written.[66] For case, authors of the Centre Kingdom could set up fictional wisdom texts in the golden age of the Old Kingdom (eastward.yard. Kagemni, Ptahhotep, and the prologue of Neferti), or they could write fictional accounts placed in a chaotic age resembling more the problematic life of the First Intermediate Period (eastward.thou. Merykare and The Eloquent Peasant).[67] Other fictional texts are fix in illo tempore (in an indeterminable era) and usually contain timeless themes.[68]

Parkinson writes that virtually all literary texts were pseudonymous, and frequently falsely attributed to well-known male protagonists of earlier history, such as kings and viziers.[70] Just the literary genres of "teaching" and "laments/discourses" contain works attributed to historical authors; texts in genres such as "narrative tales" were never attributed to a well-known historical person.[71] Tait asserts that during the Classical Menstruum of Egypt, "Egyptian scribes constructed their ain view of the history of the role of scribes and of the 'authorship' of texts", but during the Tardily Period, this function was instead maintained by the religious elite fastened to the temples.[72]

In that location are a few exceptions to the rule of pseudonymity. The real authors of some Ramesside Period instruction texts were acknowledged, but these cases are rare, localized, and practice non typify mainstream works.[73] Those who wrote individual and sometimes model letters were acknowledged equally the original authors. Private letters could be used in courts of law as testimony, since a person's unique handwriting could be identified as authentic.[74] Private messages received or written by the pharaoh were sometimes inscribed in hieroglyphics on stone monuments to celebrate kingship, while kings' decrees inscribed on stone stelas were frequently made public.[75]

Literary genres and subjects [edit]

Modernistic Egyptologists categorize Egyptian texts into genres, for example "laments/discourses" and narrative tales.[76] The only genre of literature named as such by the ancient Egyptians was the "pedagogy" or sebayt genre.[77] Parkinson states that the titles of a work, its opening argument, or key words institute in the trunk of text should exist used as indicators of its detail genre.[78] Only the genre of "narrative tales" employed prose, yet many of the works of that genre, as well as those of other genres, were written in poetry.[79] Most ancient Egyptian verses were written in couplet form, merely sometimes triplets and quatrains were used.[eighty]

Instructions and teachings [edit]

The "instructions" or "instruction" genre, as well every bit the genre of "reflective discourses", can be grouped in the larger corpus of wisdom literature found in the ancient Near East.[81] The genre is didactic in nature and is thought to have formed function of the Middle Kingdom scribal teaching syllabus.[82] However, teaching texts often incorporate narrative elements that can instruct besides as entertain.[82] Parkinson asserts that there is testify that educational activity texts were not created primarily for use in scribal education, simply for ideological purposes.[83] For example, Adolf Erman (1854–1937) writes that the fictional instruction given by Amenemhat I (r. 1991–1962 BC) to his sons "...far exceeds the bounds of school philosophy, and there is zip whatever to practise with school in a great warning his children to be loyal to the king".[84] While narrative literature, embodied in works such equally The Eloquent Peasant, emphasize the individual hero who challenges society and its accepted ideologies, the instruction texts instead stress the demand to comply with society'due south accepted dogmas.[85]

Primal words constitute in teaching texts include "to know" (rḫ) and "to teach" (sbꜣ).[81] These texts unremarkably prefer the formulaic title structure of "the instruction of 10 made for Y", where "X" tin be represented by an authoritative figure (such as a vizier or king) providing moral guidance to his son(due south).[86] It is sometimes difficult to determine how many fictional addressees are involved in these teachings, since some texts switch between singular and plural when referring to their audiences.[87]

Examples of the "teaching" genre include the Maxims of Ptahhotep, Instructions of Kagemni, Teaching for King Merykare, Instructions of Amenemhat, Education of Hardjedef, Loyalist Teaching, and Instructions of Amenemope.[88] Teaching texts that accept survived from the Eye Kingdom were written on papyrus manuscripts.[89] No educational ostraca from the Middle Kingdom have survived.[89] The primeval schoolboy'south wooden writing board, with a copy of a didactics text (i.eastward. Ptahhotep), dates to the Eighteenth dynasty.[89] Ptahhotep and Kagemni are both found on the Prisse Papyrus, which was written during the 12th dynasty of the Middle Kingdom.[90] The unabridged Loyalist Teaching survives only in manuscripts from the New Kingdom, although the entire outset half is preserved on a Middle Kingdom biographical rock stela commemorating the Twelfth dynasty official Sehetepibre.[91] Merykare, Amenemhat, and Hardjedef are genuine Middle Kingdom works, but only survive in later New Kingdom copies.[92] Amenemope is a New Kingdom compilation.[93]

Narrative tales and stories [edit]

The genre of "tales and stories" is probably the least represented genre from surviving literature of the Middle Kingdom and Middle Egyptian.[95] In Tardily Egyptian literature, "tales and stories" comprise the majority of surviving literary works dated from the Ramesside Menstruum of the New Kingdom into the Late Period.[96] Major narrative works from the Middle Kingdom include the Tale of the Courtroom of Rex Cheops, King Neferkare and Full general Sasenet, The Eloquent Peasant, Story of Sinuhe, and Tale of the shipwrecked sailor.[97] The New Kingdom corpus of tales includes the Quarrel of Apepi and Seqenenre, The Taking of Joppa, Tale of the doomed prince, Tale of Two Brothers, and the Report of Wenamun.[98] Stories from the 1st millennium BC written in Demotic include the story of the Famine Stela (set in the Old Kingdom, although written during the Ptolemaic dynasty) and brusk story cycles of the Ptolemaic and Roman periods that transform well-known historical figures such equally Khaemweset (Nineteenth Dynasty) and Inaros (First Western farsi Period) into fictional, legendary heroes.[99] This is contrasted with many stories written in Late Egyptian, whose authors oft chose divinities every bit protagonists and mythological places as settings.[51]

Parkinson defines tales as "...non-commemorative, non-functional, fictional narratives" that unremarkably employ the key word "narrate" (sdd).[95] He describes it equally the nearly open-ended genre, since the tales ofttimes comprise elements of other literary genres.[95] For example, Morenz describes the opening section of the strange run a risk tale Sinuhe as a "...funerary self-presentation" that parodies the typical autobiography found on commemorative funerary stelas.[100] The autobiography is for a courier whose service began under Amenemhat I.[101] Simpson states that the expiry of Amenemhat I in the report given by his son, coregent, and successor Senusret I (r. 1971–1926 BC) to the army in the beginning of Sinuhe is "...splendid propaganda".[102] Morenz describes The shipwrecked sailor as an expeditionary report and a travel-narrative myth.[100] Simpson notes the literary device of the story within a story in The shipwrecked crewman may provide "...the primeval examples of a narrative quarrying report".[103] With the setting of a magical desert island, and a character who is a talking ophidian, The shipwrecked sailor may also be classified every bit a fairy tale.[104] While stories like Sinuhe, Taking of Joppa, and the Doomed prince contain fictional portrayals of Egyptians abroad, the Report of Wenamun is nearly likely based on a true account of an Egyptian who traveled to Byblos in Phoenicia to obtain cedar for shipbuilding during the reign of Ramesses XI.[105]

Narrative tales and stories are most often found on papyri, but partial and sometimes complete texts are found on ostraca. For case, Sinuhe is institute on five papyri composed during the Twelfth and Thirteenth dynasties.[106] This text was subsequently copied numerous times on ostraca during the Nineteenth and Twentieth dynasties, with one ostraca containing the complete text on both sides.[106]

Laments, discourses, dialogues, and prophecies [edit]

The Center Kingdom genre of "prophetic texts", besides known as "laments", "discourses", "dialogues", and "apocalyptic literature",[107] include such works equally the Admonitions of Ipuwer, Prophecy of Neferti, and Dispute betwixt a man and his Ba. This genre had no known precedent in the Old Kingdom and no known original compositions were produced in the New Kingdom.[108] However, works like Prophecy of Neferti were frequently copied during the Ramesside Menstruation of the New Kingdom,[109] when this Eye Kingdom genre was canonized but discontinued.[110] Egyptian prophetic literature underwent a revival during the Greek Ptolemaic dynasty and Roman menses of Egypt with works such as the Demotic Chronicle, Oracle of the Lamb, Oracle of the Potter, and two prophetic texts that focus on Nectanebo 2 (r. 360–343 BC) as a protagonist.[111] Along with "teaching" texts, these cogitating discourses (key give-and-take mdt) are grouped with the wisdom literature category of the ancient Well-nigh East.[81]

In Eye Kingdom texts, connecting themes include a pessimistic outlook, descriptions of social and religious change, and cracking disorder throughout the country, taking the class of a syntactic "then-now" verse formula.[112] Although these texts are ordinarily described as laments, Neferti digresses from this model, providing a positive solution to a problematic world.[81] Although it survives only in afterward copies from the Eighteenth dynasty onward, Parkinson asserts that, due to obvious political content, Neferti was originally written during or before long afterwards the reign of Amenemhat I.[113] Simpson calls it "...a blatant political pamphlet designed to support the new authorities" of the Twelfth dynasty founded by Amenemhat, who usurped the throne from the Mentuhotep line of the Eleventh dynasty.[114] In the narrative discourse, Sneferu (r. 2613–2589 BC) of the Fourth dynasty summons to court the sage and lector priest Neferti. Neferti entertains the king with prophecies that the country volition enter into a chaotic historic period, alluding to the Outset Intermediate Period, only to be restored to its former glory past a righteous king— Ameny—whom the ancient Egyptian would readily recognize equally Amenemhat I.[115] A like model of a tumultuous earth transformed into a gilded historic period by a savior king was adopted for the Lamb and Potter, although for their audiences living under Roman domination, the savior was withal to come.[116]

Although written during the Twelfth dynasty, Ipuwer only survives from a Nineteenth dynasty papyrus. However, A human being and his Ba is found on an original Twelfth dynasty papyrus, Papyrus Berlin 3024.[117] These two texts resemble other discourses in style, tone, and subject field matter, although they are unique in that the fictional audiences are given very active roles in the substitution of dialogue.[118] In Ipuwer, a sage addresses an unnamed rex and his attendants, describing the miserable state of the land, which he blames on the rex'south inability to uphold royal virtues. This can exist seen either as a warning to kings or every bit a legitimization of the current dynasty, contrasting information technology with the supposedly turbulent catamenia that preceded it.[119] In A man and his Ba, a man recounts for an audience a chat with his ba (a component of the Egyptian soul) on whether to continue living in despair or to seek death as an escape from misery.[120]

Poems, songs, hymns, and afterlife texts [edit]

The funerary rock slab stela was first produced during the early Old Kingdom. Unremarkably establish in mastaba tombs, they combined raised-relief artwork with inscriptions bearing the name of the deceased, their official titles (if whatsoever), and invocations.[121]

Funerary poems were idea to preserve a monarch'south soul in death. The Pyramid Texts are the earliest surviving religious literature incorporating poetic poesy.[122] These texts do not appear in tombs or pyramids originating earlier the reign of Unas (r. 2375–2345 BC), who had the Pyramid of Unas built at Saqqara.[122] The Pyramid Texts are chiefly concerned with the role of preserving and nurturing the soul of the sovereign in the afterlife.[122] This aim somewhen included safeguarding both the sovereign and his subjects in the afterlife.[123] A variety of textual traditions evolved from the original Pyramid Texts: the Coffin Texts of the Middle Kingdom,[124] the so-called Book of the Expressionless, Litany of Ra, and Amduat written on papyri from the New Kingdom until the end of ancient Egyptian civilization.[125]

Poems were also written to celebrate kingship. For example, at the Precinct of Amun-Re at Karnak, Thutmose III (r. 1479–1425 BC) of the Eighteenth dynasty erected a stela commemorating his military victories in which the gods bless Thutmose in poetic poetry and ensure for him victories over his enemies.[126] In addition to stone stelas, poems have been found on wooden writing boards used by schoolboys.[127] Besides the glorification of kings,[128] poems were written to honor various deities, and even the Nile.[129]

Surviving hymns and songs from the Old Kingdom include the morning greeting hymns to the gods in their corresponding temples.[130] A cycle of Middle-Kingdom songs dedicated to Senusret Three (r. 1878–1839 BC) have been discovered at El-Lahun.[131] Erman considers these to be secular songs used to greet the pharaoh at Memphis,[132] while Simpson considers them to be religious in nature merely affirms that the partition between religious and secular songs is non very sharp.[131] The Harper's Song, the lyrics found on a tombstone of the Centre Kingdom and on Papyrus Harris 500 from the New Kingdom, was to be performed for dinner guests at formal banquets.[133]

During the reign of Akhenaten (r. 1353–1336 BC), the Slap-up Hymn to the Aten—preserved in tombs of Amarna, including the tomb of Ay—was written to the Aten, the sun-disk deity given exclusive patronage during his reign.[134] Simpson compares this limerick's wording and sequence of ideas to those of Psalm 104.[135]

Merely a single poetic hymn in the Demotic script has been preserved.[136] However, there are many surviving examples of Late-Period Egyptian hymns written in hieroglyphs on temple walls.[137]

No Egyptian beloved vocal has been dated from earlier the New Kingdom, these being written in Late Egyptian, although information technology is speculated that they existed in previous times.[138] Erman compares the love songs to the Song of Songs, citing the labels "sister" and "brother" that lovers used to address each other.[139]

Private messages, model messages, and epistles [edit]

The ancient Egyptian model letters and epistles are grouped into a single literary genre. Papyrus rolls sealed with mud stamps were used for long-distance letters, while ostraca were ofttimes used to write shorter, non-confidential letters sent to recipients located nearby.[140] Letters of royal or official correspondence, originally written in hieratic, were sometimes given the exalted condition of being inscribed on rock in hieroglyphs.[141] The diverse texts written past schoolboys on wooden writing boards include model letters.[89] Private letters could be used as epistolary model messages for schoolboys to copy, including letters written by their teachers or their families.[142] However, these models were rarely featured in educational manuscripts; instead fictional messages found in numerous manuscripts were used.[143] The common epistolary formula used in these model letters was "The official A. saith to the scribe B".[144]

The oldest-known private letters on papyrus were institute in a funerary temple dating to the reign of Djedkare-Izezi (r. 2414–2375 BC) of the Fifth dynasty.[145] More messages are dated to the Sixth dynasty, when the epistle subgenre began.[146] The educational text Book of Kemit, dated to the Eleventh dynasty, contains a list of epistolary greetings and a narrative with an ending in letter of the alphabet course and suitable terminology for use in commemorative biographies.[147] Other letters of the early Eye Kingdom have also been found to use epistolary formulas similar to the Book of Kemit.[148] The Heqanakht papyri, written by a gentleman farmer, date to the Eleventh dynasty and represent some of the lengthiest private messages known to take been written in ancient Egypt.[69]

During the late Heart Kingdom, greater standardization of the epistolary formula can exist seen, for example in a series of model letters taken from dispatches sent to the Semna fortress of Nubia during the reign of Amenemhat III (r. 1860–1814 BC).[149] Epistles were also written during all three dynasties of the New Kingdom.[150] While letters to the dead had been written since the One-time Kingdom, the writing of petition letters in epistolary form to deities began in the Ramesside Period, becoming very popular during the Western farsi and Ptolemaic periods.[151]

The epistolary Satirical Letter of the alphabet of Papyrus Anastasi I written during the Nineteenth dynasty was a pedagogical and didactic text copied on numerous ostraca by schoolboys.[152] Wente describes the versatility of this epistle, which contained "...proper greetings with wishes for this life and the adjacent, the rhetoric composition, interpretation of aphorisms in wisdom literature, awarding of mathematics to engineering issues and the calculation of supplies for an ground forces, and the geography of western asia".[153] Moreover, Wente calls this a "...polemical tractate" that counsels against the rote, mechanical learning of terms for places, professions, and things; for example, it is non acceptable to know just the identify names of southwest asia, but likewise of import details about its topography and routes.[153] To enhance the teaching, the text employs sarcasm and irony.[153]

Biographical and autobiographical texts [edit]

Catherine Parke, Professor Emerita of English and Women'southward Studies at the University of Missouri in Columbia, Missouri, writes that the earliest "commemorative inscriptions" belong to ancient Egypt and date to the third millennium BC.[154] She writes: "In aboriginal Arab republic of egypt the formulaic accounts of Pharaoh's lives praised the continuity of dynastic power. Although typically written in the beginning person, these pronouncements are public, general testimonials, not personal utterances."[155] She adds that as in these ancient inscriptions, the human urge to "...celebrate, commemorate, and immortalize, the impulse of life against death", is the aim of biographies written today.[155]

A funerary stela of a homo named Ba (seated, sniffing a sacred lotus while receiving libations); Ba'due south son Mes and wife Iny are also seated. The identity of the cooler bearer is unspecified. The stela is dated to the Eighteenth dynasty of the New Kingdom period.

Olivier Perdu, a professor of Egyptology at the Collège de France, states that biographies did not exist in ancient Egypt, and that commemorative writing should exist considered autobiographical.[156] Edward 50. Greenstein, Professor of Bible at the Tel Aviv University and Bar-Ilan University, disagrees with Perdu's terminology, stating that the ancient world produced no "autobiographies" in the mod sense, and these should be distinguished from 'autobiographical' texts of the ancient world.[157] However, both Perdu and Greenstein assert that autobiographies of the ancient Near Eastward should not be equated with the modern concept of autobiography.[158]

In her word of the Ecclesiastes of the Hebrew Bible, Jennifer Koosed, associate professor of Faith at Albright College, explains that there is no solid consensus among scholars equally to whether true biographies or autobiographies existed in the ancient world.[159] One of the major scholarly arguments against this theory is that the concept of individuality did not exist until the European Renaissance, prompting Koosed to write "...thus autobiography is made a product of European civilisation: Augustine begat Rosseau begat Henry Adams, and and then on".[159] Koosed asserts that the use of first-person "I" in aboriginal Egyptian commemorative funerary texts should not be taken literally since the supposed author is already dead. Funerary texts should be considered biographical instead of autobiographical.[158] Koosed cautions that the term "biography" practical to such texts is problematic, since they as well usually describe the deceased person's experiences of journeying through the afterlife.[158]

Starting time with the funerary stelas for officials of the late Third dynasty, small amounts of biographical particular were added next to the deceased men'southward titles.[160] Still, it was not until the 6th dynasty that narratives of the lives and careers of government officials were inscribed.[161] Tomb biographies became more detailed during the Middle Kingdom, and included information well-nigh the deceased person'southward family.[162] The vast majority of autobiographical texts are dedicated to scribal bureaucrats, but during the New Kingdom some were dedicated to armed services officers and soldiers.[163] Autobiographical texts of the Tardily Period place a greater stress upon seeking help from deities than interim righteously to succeed in life.[164] Whereas before autobiographical texts exclusively dealt with celebrating successful lives, Late Period autobiographical texts include laments for premature death, similar to the epitaphs of aboriginal Greece.[165]

Decrees, chronicles, king lists, and histories [edit]

Modern historians consider that some biographical—or autobiographical—texts are important historical documents.[166] For example, the biographical stelas of military generals in tomb chapels congenital nether Thutmose Iii provide much of the information known almost the wars in Syria and Palestine.[167] However, the annals of Thutmose 3, carved into the walls of several monuments built during his reign, such as those at Karnak, too preserve data about these campaigns.[168] The annals of Ramesses Ii (r. 1279–1213 BC), recounting the Boxing of Kadesh against the Hittites include, for the first time in Egyptian literature, a narrative epic poem, distinguished from all earlier poetry, which served to celebrate and instruct.[169]

Other documents useful for investigating Egyptian history are aboriginal lists of kings plant in terse chronicles, such as the Fifth dynasty Palermo stone.[170] These documents legitimated the contemporary pharaoh's claim to sovereignty.[171] Throughout ancient Egyptian history, regal decrees recounted the deeds of ruling pharaohs.[172] For instance, the Nubian pharaoh Piye (r. 752–721 BC), founder of the Twenty-5th Dynasty, had a stela erected and written in classical Center Egyptian that describes with unusual nuances and vivid imagery his successful military campaigns.[173]

An Egyptian historian, known by his Greek name as Manetho (c. 3rd century BC), was the first to compile a comprehensive history of Arab republic of egypt.[174] Manetho was active during the reign of Ptolemy II (r. 283–246 BC) and used The Histories past the Greek Herodotus (c. 484 BC–c. 425 BC) equally his primary source of inspiration for a history of Arab republic of egypt written in Greek.[174] However, the primary sources for Manetho's work were the king list chronicles of previous Egyptian dynasties.[171]

Tomb and temple graffiti [edit]

Fischer-Elfert distinguishes ancient Egyptian graffiti writing as a literary genre.[175] During the New Kingdom, scribes who traveled to ancient sites often left graffiti messages on the walls of sacred mortuary temples and pyramids, usually in commemoration of these structures.[176] Modern scholars do not consider these scribes to have been mere tourists, just pilgrims visiting sacred sites where the extinct cult centers could be used for communicating with the gods.[177] There is evidence from an educational ostracon institute in the tomb of Senenmut (TT71) that formulaic graffiti writing was expert in scribal schools.[177] In 1 graffiti bulletin, left at the mortuary temple of Thutmose III at Deir el-Bahri, a modified saying from The Maxims of Ptahhotep is incorporated into a prayer written on the temple wall.[178] Scribes usually wrote their graffiti in separate clusters to distinguish their graffiti from others'.[175] This led to competition amidst scribes, who would sometimes denigrate the quality of graffiti inscribed by others, even ancestors from the scribal profession.[175]

Legacy, translation and interpretation [edit]

After the Copts converted to Christianity in the first centuries AD, their Coptic Christian literature became separated from the pharaonic and Hellenistic literary traditions.[179] Nevertheless, scholars speculate that aboriginal Egyptian literature, peradventure in oral form, influenced Greek and Standard arabic literature. Parallels are drawn betwixt the Egyptian soldiers sneaking into Jaffa hidden in baskets to capture the metropolis in the story The Taking of Joppa and the Mycenaean Greeks sneaking into Troy inside the Trojan Horse.[180] The Taking of Joppa has too been compared to the Arabic story of Ali Baba in One Grand and One Nights.[181] It has been conjectured that Sinbad the Crewman may take been inspired by the pharaonic Tale of the shipwrecked sailor.[182] Some Egyptian literature was commented on by scholars of the ancient world. For example, the Jewish Roman historian Josephus (37–c. 100 Advertizement) quoted and provided commentary on Manetho's historical texts.[183]

The virtually recently carved hieroglyphic inscription of ancient Arab republic of egypt known today is plant in a temple of Philae, dated precisely to 394 AD during the reign of Theodosius I (r. 379–395 AD).[184] In the 4th century AD, the Hellenized Egyptian Horapollo compiled a survey of well-nigh two hundred Egyptian hieroglyphs and provided his interpretation of their meanings, although his understanding was express and he was unaware of the phonetic uses of each hieroglyph.[185] This survey was apparently lost until 1415, when the Italian Cristoforo Buondelmonti acquired information technology at the island of Andros.[185] Athanasius Kircher (1601–1680) was the first in Europe to realize that Coptic was a directly linguistic descendant of aboriginal Egyptian.[185] In his Oedipus Aegyptiacus, he made the first concerted European attempt to interpret the meaning of Egyptian hieroglyphs, albeit based on symbolic inferences.[185]

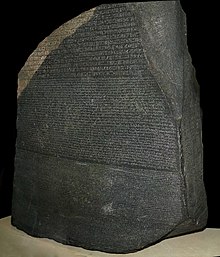

It was non until 1799, with the Napoleonic discovery of a trilingual (i.e. hieroglyphic, Demotic, Greek) stela inscription on the Rosetta Stone, that modernistic scholars were able to decipher aboriginal Egyptian literature.[186] The commencement major effort to translate the hieroglyphs of the Rosetta Stone was made by Jean-François Champollion (1790–1832) in 1822.[187] The earliest translation efforts of Egyptian literature during the 19th century were attempts to confirm Biblical events.[187]

Before the 1970s, scholarly consensus was that ancient Egyptian literature—although sharing similarities with modern literary categories—was not an independent discourse, uninfluenced past the aboriginal sociopolitical lodge.[188] All the same, from the 1970s onwards, a growing number of historians and literary scholars have questioned this theory.[189] While scholars earlier the 1970s treated aboriginal Egyptian literary works as viable historical sources that accurately reflected the conditions of this ancient society, scholars at present circumspection against this arroyo.[190] Scholars are increasingly using a multifaceted hermeneutic approach to the written report of individual literary works, in which not only the style and content, merely also the cultural, social and historical context of the work are taken into account.[189] Individual works can then exist used as case studies for reconstructing the main features of ancient Egyptian literary discourse.[189]

Notes [edit]

- ^ Foster 2001, p. xx.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 64–66.

- ^ Forman & Quirke 1996, p. 26.

- ^ Wilson 2003, pp. 7–10; Forman & Quirke 1996, pp. 10–12; Wente 1990, p. 2; Allen 2000, pp. 1–2, six.

- ^ Wilson 2003, p. 28; Forman & Quirke 1996, p. 13; Allen 2000, p. 3.

- ^ Forman & Quirke 1996, p. thirteen; for similar examples, see Allen (2000: three) and Erman (2005: xxxv-xxxvi).

- ^ Wilkinson 2000, pp. 23–24; Wilson 2004, p. 11; Gardiner 1915, p. 72.

- ^ Wilson 2003, pp. 22, 47; Forman & Quirke 1996, pp. 10; Wente 1990, p. 2; Parkinson 2002, p. 73.

- ^ Forman & Quirke 1996, p. 10.

- ^ Wilson 2003, pp. 63–64.

- ^ a b c Wilson 2003, p. 71; Forman & Quirke 1996, pp. 101–103.

- ^ Erman 2005, p. xxxvii; Simpson 1972, pp. viii–9; Forman & Quirke 1996, p. 19; Allen 2000, p. half-dozen.

- ^ a b Forman & Quirke 1996, p. nineteen.

- ^ Wilson 2003, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Wilson 2003, pp. 22–23, 91–92; Parkinson 2002, p. 73; Wente 1990, pp. 1–ii; Spalinger 1990, p. 297; Allen 2000, p. 6.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 73–74; Forman & Quirke 1996, p. 19.

- ^ a b Forman & Quirke 1996, p. 17.

- ^ Forman & Quirke 1996, pp. 17–19, 169; Allen 2000, p. half-dozen.

- ^ Forman & Quirke 1996, pp. 19, 169; Allen 2000, p. 6; Simpson 1972, pp. eight–9; Erman 2005, pp. xxxvii, xlii; Foster 2001, p. xv.

- ^ a b Wente 1990, p. 4.

- ^ a b Wente 1990, pp. 4–five.

- ^ Allen 2000, p. v; Foster 2001, p. xv; encounter also Wente 1990, pp. 5–6 for a wooden writing board example.

- ^ a b c Forman & Quirke 1996, p. 169.

- ^ a b Quirke 2004, p. 14.

- ^ Wente 1990, pp. 2–3; Tait 2003, pp. ix–10.

- ^ Wente 1990, pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b c Tait 2003, pp. 9–ten.

- ^ a b Wilson 2003, pp. 91–93.

- ^ Wilson 2003, pp. 91–93; run into as well Wente 1990, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Tait 2003, p. 10; see besides Parkinson 2002, pp. 298–299.

- ^ a b c Fischer-Elfert 2003, p. 121.

- ^ Simpson 1972, pp. 3–4; Foster 2001, pp. xvii–xviii.

- ^ a b c Allen 2000, p. 1.

- ^ Allen 2000, p. 1; Fischer-Elfert 2003, p. 119; Erman 2005, pp. xxv–xxvi.

- ^ Allen 2000, p. 1; Wildung 2003, p. 61.

- ^ Allen 2000, p. 6.

- ^ Allen 2000, pp. 1, 5–half dozen; Wildung 2003, p. 61; Erman 2005, pp. xxv–xxvii; Lichtheim 1980, p. iv.

- ^ Allen 2000, p. 5; Erman 2005, pp. xxv–xxvii; Lichtheim 1980, p. 4.

- ^ Wildung 2003, p. 61.

- ^ Wente 1990, pp. 6–7; encounter also Wilson 2003, pp. 19–xx, 96–97; Erman 2005, pp. xxvii–xxviii.

- ^ Wilson 2003, p. 96.

- ^ Wente 1990, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Wente 1990, pp. 7–8; Parkinson 2002, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Wilson 2003, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Wilson 2003, p. 95.

- ^ Wilson 2003, pp. 96–98.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Fischer-Elfert 2003, pp. 119–121; Parkinson 2002, p. fifty.

- ^ Wilson 2003, pp. 97–98; run into Parkinson 2002, pp. 53–54; see also Fischer-Elfert 2003, pp. 119–121.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 54–55; see also Morenz 2003, p. 104.

- ^ a b Simpson 1972, pp. 5–half-dozen.

- ^ Fischer-Elfert 2003, p. 122.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 78–79; for pictures (with captions) of Egyptian miniature funerary models of boats with men reading papyrus texts aloud, see Forman & Quirke 1996, pp. 76–77, 83.

- ^ a b c Parkinson 2002, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Wilson 2003, p. 93.

- ^ a b Parkinson 2002, pp. 80–81.

- ^ a b Forman & Quirke 1996, pp. 51–56, 62–63, 68–72, 111–112; Budge 1972, pp. 240–243.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, p. seventy.

- ^ Wente 1990, pp. one, nine, 132–133.

- ^ Wente 1990, p. 9.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 45–46, 49–l, 55–56; Morenz 2003, p. 102; see too Simpson 1972, pp. 3–6 and Erman 2005, pp. xxiv–xxv.

- ^ a b Morenz 2003, p. 102.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 45–46, 49–fifty, 55–56; Morenz 2003, p. 102.

- ^ a b Parkinson 2002, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 45–46; Morenz 2003, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, p. 46.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 46–47; run across besides Morenz 2003, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Morenz 2003, pp. 104–107.

- ^ a b Wente 1990, pp. 54–55, 58–63.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 75–76; Fischer-Elfert 2003, p. 120.

- ^ Tait 2003, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 238–239.

- ^ Wente 1990, p. seven.

- ^ Wente 1990, pp. 17–xviii.

- ^ Fischer-Elfert 2003, pp. 122–123; Simpson 1972, p. iii.

- ^ Fischer-Elfert 2003, pp. 122–123; Simpson 1972, pp. 5–vi; Parkinson 2002, p. 110.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Foster 2001, pp. xv–16.

- ^ Foster 2001, p. xvi.

- ^ a b c d Parkinson 2002, p. 110.

- ^ a b Parkinson 2002, pp. 110, 235.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 236–237.

- ^ Erman 2005, p. 54.

- ^ Loprieno 1996, p. 217.

- ^ Simpson 1972, p. 6; see also Parkinson 2002, pp. 236–238.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 237–238.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 313–319; Simpson 1972, pp. 159–200, 241–268.

- ^ a b c d Parkinson 2002, pp. 235–236.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 313–315; Simpson 1972, pp. 159–177.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 318–319.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 313–314, 315–317; Simpson 1972, pp. 180, 193.

- ^ Simpson 1972, p. 241.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 295–296.

- ^ a b c Parkinson 2002, p. 109.

- ^ Fischer-Elfert 2003, p. 120.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 294–299; Simpson 1972, pp. 15–76; Erman 2005, pp. xiv–52.

- ^ Simpson 1972, pp. 77–158; Erman 2005, pp. 150–175.

- ^ Gozzoli 2006, pp. 247–249; for another source on the Dearth Stela, see Lichtheim 1980, pp. 94–95.

- ^ a b Morenz 2003, pp. 102–104.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 297–298.

- ^ Simpson 1972, p. 57.

- ^ Simpson 1972, p. fifty; encounter also Foster 2001, p. eight.

- ^ Foster 2001, p. 8.

- ^ Simpson 1972, pp. 81, 85, 87, 142; Erman 2005, pp. 174–175.

- ^ a b Simpson 1972, p. 57 states that there are two Center-Kingdom manuscripts for Sinuhe, while the updated work of Parkinson 2002, pp. 297–298 mentions 5 manuscripts.

- ^ Simpson 1972, pp. half dozen–7; Parkinson 2002, pp. 110, 193; for "apocalyptic" designation, see Gozzoli 2006, p. 283.

- ^ Morenz 2003, p. 103.

- ^ Simpson 1972, pp. vi–vii.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 232–233.

- ^ Gozzoli 2006, pp. 283–304; see too Parkinson 2002, p. 233, who alludes to this genre being revived in periods after the Eye Kingdom and cites Depauw (1997: 97–9), Frankfurter (1998: 241–viii), and Bresciani (1999).

- ^ Simpson 1972, pp. vii–viii; Parkinson 2002, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 45–46, 49–50, 303–304.

- ^ Simpson 1972, p. 234.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 197–198, 303–304; Simpson 1972, p. 234; Erman 2005, p. 110.

- ^ Gozzoli 2006, pp. 301–302.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 308–309; Simpson 1972, pp. 201, 210.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, pp. 111, 308–309.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, p. 308; Simpson 1972, p. 210; Erman 2005, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Parkinson 2002, p. 309; Simpson 1972, p. 201; Erman 2005, p. 86.

- ^ Bard & Shubert 1999, p. 674.

- ^ a b c Forman & Quirke 1996, pp. 48–51; Simpson 1972, pp. 4–5, 269; Erman 2005, pp. one–ii.

- ^ Forman & Quirke 1996, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Forman & Quirke 1996, pp. 65–109.

- ^ Forman & Quirke 1996, pp. 109–165.

- ^ Simpson 1972, p. 285.

- ^ Erman 2005, p. 140.

- ^ Erman 2005, pp. 254–274.

- ^ Erman 2005, pp. 137–146, 281–305.

- ^ Erman 2005, p. 10.

- ^ a b Simpson 1972, p. 279; Erman 2005, p. 134.

- ^ Erman 2005, p. 134.

- ^ Simpson 1972, p. 297; Erman 2005, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Erman 2005, pp. 288–289; Foster 2001, p. 1.

- ^ Simpson 1972, p. 289.

- ^ Tait 2003, p. 10.

- ^ Lichtheim 1980, p. 104.

- ^ Simpson 1972, pp. 7, 296–297; Erman 2005, pp. 242–243; run into likewise Foster 2001, p. 17.

- ^ Erman 2005, pp. 242–243.

- ^ Wente 1990, pp. 2, 4–v.

- ^ Wilson 2003, pp. 91–92; Wente 1990, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Erman 2005, p. 198; encounter also Lichtheim 2006, p. 167.

- ^ Erman 2005, pp. 198, 205.

- ^ Erman 2005, p. 205.

- ^ Wente 1990, p. 54.

- ^ Wente 1990, pp. 15, 54.

- ^ Wente 1990, p. 15.

- ^ Wente 1990, p. 55.

- ^ Wente 1990, p. 68.

- ^ Wente 1990, p. 89.

- ^ Wente 1990, p. 210.

- ^ Wente 1990, p. 98.

- ^ a b c Wente 1990, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Parke 2002, pp. xxi, one–ii.

- ^ a b Parke 2002, pp. one–two.

- ^ Perdu 1995, p. 2243.

- ^ Greenstein 1995, p. 2421.

- ^ a b c Koosed 2006, p. 29.

- ^ a b Koosed 2006, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Breasted 1962, pp. v–6; encounter also Foster 2001, p. xv.

- ^ Breasted 1962, pp. 5–6; see besides Bard & Shubert 1999, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Breasted 1962, pp. five–6.

- ^ Lichtheim 2006, p. 11.

- ^ Lichtheim 1980, p. five.

- ^ Lichtheim 1980, p. vi.

- ^ Gozzoli 2006, pp. ane–8.

- ^ Breasted 1962, pp. 12–thirteen.

- ^ Seters 1997, p. 147.

- ^ Lichtheim 2006, p. 6.

- ^ Gozzoli 2006, pp. i–8; Brewer & Teeter 1999, pp. 27–28; Bard & Shubert 1999, p. 36.

- ^ a b Bard & Shubert 1999, p. 36.

- ^ Lichtheim 1980, p. 7; Bard & Shubert 1999, p. 36.

- ^ Lichtheim 1980, p. seven.

- ^ a b Gozzoli 2006, pp. viii, 191–225; Brewer & Teeter 1999, pp. 27–28; Lichtheim 1980, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Fischer-Elfert 2003, p. 133.

- ^ Fischer-Elfert 2003, p. 131.

- ^ a b Fischer-Elfert 2003, p. 132.

- ^ Fischer-Elfert 2003, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Bard & Shubert 1999, p. 76.

- ^ Simpson 1972, p. 81.

- ^ Mokhtar 1990, pp. 116–117; Simpson 1972, p. 81.

- ^ Mokhtar 1990, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Gozzoli 2006, pp. 192–193, 224.

- ^ Wilson 2003, pp. 104–105; Foster 2001, pp. 14–xv.

- ^ a b c d Wilson 2003, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Wilson 2003, pp. 105–106.

- ^ a b Foster 2001, p. xii-thirteen.

- ^ Loprieno 1996, pp. 211–212.

- ^ a b c Loprieno 1996, pp. 212–213.

- ^ Loprieno 1996, pp. 211, 213.

References [edit]

- Allen, James P. (2000), Center Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Civilisation of Hieroglyphs, Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press, ISBN0-521-65312-half-dozen

- Bard, Katherine A.; Shubert, Steven Blake (1999), Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt, New York and London: Routledge, ISBN0-415-18589-0

- Breasted, James Henry (1962), Ancient Records of Arab republic of egypt: Vol. I, The Commencement to the Seventeenth Dynasties, & Vol. II, the Eighteenth Dynasty, New York: Russell & Russell, ISBN0-8462-0134-eight

- Brewer, Douglas J.; Teeter, Emily (1999), Egypt and the Egyptians, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN0-521-44518-three

- Budge, East. A. Wallis (1972), The Dwellers on the Nile: Chapters on the Life, History, Faith, and Literature of the Aboriginal Egyptians, New York: Benjamin Blom

- Erman, Adolf (2005), Ancient Egyptian Literature: A Collection of Poems, Narratives and Manuals of Instructions from the Third and Second Millennia BC, translated by Aylward 1000. Blackman, New York: Kegan Paul, ISBN0-7103-0964-3

- Fischer-Elfert, Hans-Due west. (2003), "Representations of the Past in the New Kingdom Literature", in Tait, John W. (ed.), 'Never Had the Like Occurred': Egypt's View of Its Past, London: University Higher London, Institute of Archeology, an banner of Cavendish Publishing Limited, pp. 119–138, ISBN1-84472-007-1

- Forman, Werner; Quirke, Stephen (1996), Hieroglyphs and the Afterlife in Ancient Arab republic of egypt, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN0-8061-2751-1

- Foster, John Lawrence (2001), Ancient Egyptian Literature: An Anthology, Austin: University of Texas Press, ISBN0-292-72527-2

- Gardiner, Alan H. (1915), "The Nature and Development of the Egyptian Hieroglyphic Writing", The Journal of Egyptian Archeology, 2 (ii): 61–75, doi:10.2307/3853896, JSTOR 3853896

- Gozzoli, Roberto B. (2006), The Writings of History in Ancient Egypt during the Start Millennium BC (ca. 1070–180 BC): Trends and Perspectives, London: Gilt House Publications, ISBN0-9550256-three-X

- Greenstein, Edward L. (1995), "Autobiographies in Ancient Western Asia", Civilizations of the Ancient Near East, New York: Scribner, pp. 2421–2432

- Koosed, Jennifer Fifty. (2006), (Per)mutations of Qohelet: Reading the Trunk in the Book, New York and London: T & T Clark International (Continuum imprint), ISBN0-567-02632-9

- Lichtheim, Miriam (1980), Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume III: The Late Menstruation, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN0-520-04020-i

- Lichtheim, Miriam (2006), Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume Two: The New Kingdom, with a new foreword by Hans-W. Fischer-Elfert, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN0-520-24843-0

- Loprieno, Antonio (1996), "Defining Egyptian Literature: Aboriginal Texts and Mod Literary Theory", in Cooper, Jerrold S.; Schwartz, Glenn One thousand. (eds.), The Written report of the Ancient Near East in the 21st Century, The William Foxwell Albright Centennial Conference, Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, pp. 209–250, ISBN0-931464-96-X

- Mokhtar, Yard. (1990), General History of Africa II: Aboriginal Civilizations of Africa (Abridged ed.), Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN92-3-102585-half-dozen

- Morenz, Ludwid D. (2003), "Literature equally a Structure of the By in the Middle Kingdom", in Tait, John Westward. (ed.), 'Never Had the Like Occurred': Egypt'due south View of Its By, translated by Martin Worthington, London: University College London, Institute of Archeology, an imprint of Cavendish Publishing Express, pp. 101–118, ISBN1-84472-007-1

- Parke, Catherine Neal (2002), Biography: Writing Lives, New York and London: Routledge, ISBN0-415-93892-9

- Parkinson, R. B. (2002), Poesy and Civilization in Middle Kingdom Egypt: A Dark Side to Perfection, London: Continuum, ISBN0-8264-5637-5

- Quirke, Due south. (2004), Egyptian Literature 1800 BC, questions and readings, London: Golden House Publications, ISBN0-9547218-6-one

- Perdu, Olivier (1995), "Aboriginal Egyptian Autobiographies", in Sasson, Jack (ed.), Civilizations of the Ancient Near East, New York: Scribner, pp. 2243–2254

- Seters, John Van (1997), In Search of History: Historiography in the Ancient World and the Origins of Biblical History, New Haven: Yale University Press, ISBNi-57506-013-2

- Simpson, William Kelly (1972), Simpson, William Kelly (ed.), The Literature of Aboriginal Egypt: An Anthology of Stories, Instructions, and Poetry, translations by R.O. Faulkner, Edward F. Wente, Jr., and William Kelly Simpson, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, ISBN0-300-01482-1

- Spalinger, Anthony (1990), "The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus as a Historical Document", Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur, 17: 295–337

- Tait, John Westward. (2003), "Introduction—'...Since the Fourth dimension of the Gods'", in Tait, John (ed.), 'Never Had the Like Occurred': Egypt's View of Its Past, London: University College London, Institute of Archaeology, an banner of Cavendish Publishing Limited, pp. 1–14, ISBNi-84472-007-1

- Wente, Edward F. (1990), Meltzer, Edmund S. (ed.), Letters from Ancient Arab republic of egypt, translated by Edward F. Wente, Atlanta: Scholars Press, Society of Biblical Literature, ISBN1-55540-472-iii

- Wildung, Dietrich (2003), "Looking Back into the Future: The Eye Kingdom equally a Span to the By", in Tait, John (ed.), 'Never Had the Like Occurred': Arab republic of egypt's View of Its Past, London: Academy College London, Institute of Archaeology, an imprint of Cavendish Publishing Limited, pp. 61–78, ISBN1-84472-007-1

- Wilkinson, Toby A. H. (2000), "What a King Is This: Narmer and the Concept of the Ruler", The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 86: 23–32, doi:10.2307/3822303, JSTOR 3822303

- Wilson, Penelope (2003), Sacred Signs: Hieroglyphs in Ancient Arab republic of egypt , Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN0-19-280299-two

- Wilson, Penelope (2004), Hieroglyphs: A Very Brusk Introduction, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN0-xix-280502-9

External links [edit]

- Internet Ancient History Source Book: Arab republic of egypt (by Fordham University, NY)

- The Language of Aboriginal Arab republic of egypt (by Belgian Egyptologist Jacques Kinnaer)

- Volume: Literature of the Ancient Egyptians, Readable HTML format

- The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Literature of the Aboriginal Egyptians (Due east. A. Wallis Budge)

- Academy of Texas Press - Ancient Egyptian Literature: An Anthology (2001) (The unabridged preface, by John Fifty. Foster)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Egyptian_literature

Post a Comment for "Who Was the First Person to Read Old Egyptian Writings"